The Demon Slayer

Ranjan Ghosh's new film Mahishasura Marddini, presents a different perspective

Goddess Durga astride her beautiful lion, along with her four children, Kartik, Ganesh, Lakshmi and Saraswati along with Mahishasura may be seen at the annual festival in Bengal. But it is no longer seasonal so far as Bengali cinema is concerned.

The Mother Goddess and her divine company astride her lion is omnipresent in Bengali films right through the year. Aparna Sen opened her strongly feminist film Parama around the Durga Pooja. Rituparna Ghosh's Utsav revolved around the Durga Pooja being celebrated in an ancestral home which forms the base for a family reunion. Avijatrik directed by Subhrajit Mitra which won the National Award for the Best Bengali film, focuses on the Durga Pooja when Apu visits his ancestral village Boral, happening in a neighbor's home. Koushik Ganguli made two films where the Durga Pooja played a critical role, and Arindam Sil made one film.

Whether Durga is used as a strategy to raise the commercial prospects of a film, or, whether the festival offers a wonderful backdrop for any story to unfold is left to the audience to judge.

Ranjan Ghosh's new film Mahishasura Marddini, however, presents a different perspective where Durga Pooja becomes a more important peg than the Pooja itself. In fact, the Pooja does not actually happen in the film.

The Pooja becomes a platform to reflect that though we have a supreme Goddess Mother we wait for eagerly the entire year, and worship her like we never worship other Gods of the Hindu pantheon, we, as humans, do not spare a second before gang-raping a little orphan girl who lives off pickings from dumps, and then burning her alive; or, abandon a new born female into a dirt-filled dump to die; or, for a husband to accuse his wife about lying about her abductors not having raped her; or, a wife being battered by the husband; but a young woman immersed in preparing for her exams cannot be bothered and slams the door on her face.

"I doubt if Maa Durga will send her daughters from next year. The world has become a danger zone for girls," says one young man jokingly in the beautiful antique mansion where he, along with two girls and another young student, live with a young and beautiful landlady (Rituparna Sengupta). They are celebrating Durga Pooja together, just off the courtyard of the mansion. Another retorts, "I think even Maa Durga might cancel her annual visit on earth from next year." Though it would seem they are joking, the credits shot against a moving collage of newspaper headlines reporting cases of gang-rape, murder, female infanticide suggest what the film is all about.

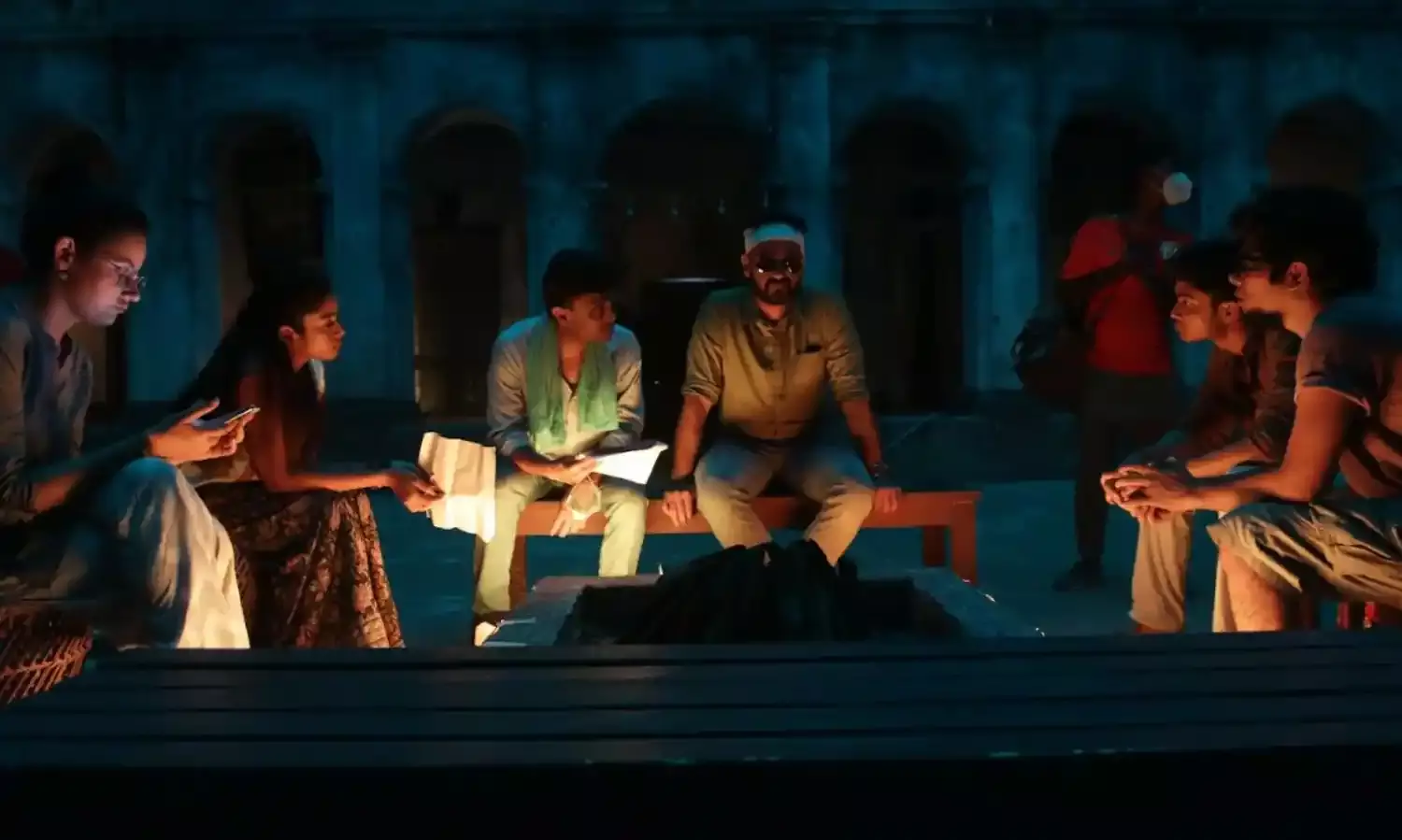

The story is limited to one night when many things happen in the courtyard of the ancestral mansion on the eve of the Pooja's first night called Bodhon, meaning, "inauguration." The artisan is putting finishing touches to the idol but leaves with his two young helpers as it is too late. The four youngsters, all students who have just graduated in different disciplines waiting to begin their professional lives, are left to put the finishing touches to the idols.

The beautiful landlady steps in. We learn that she has been a pilot and when this story happens, she is preparing to become the country's first female astronaut! She has snatched four days of leave to celebrate the festival with her four young tenants with whom she shares a warm and healthy relationship. A few flashbacks reveal the bias against girls and women in which girls and women are also at fault and men alone are not perpetrators of dehumanizing the female of the species.

As the film moves on, in the spacious courtyard with a fire aflame in the centre, incidents, arguments and debates happen as other people step in, symbolising faces of patriarchy in varied shapes and colours. All of them in some way or another, seem to be shocked by the gang-rape and murder of the little girl but one keeps wondering whether the debates boil down to plastic sympathy or whether they spring from genuine concern about the inhuman killing and rape of the little girl.

One of them is an influential politician (Saswata Chatterjee) who was once married to the beautiful landlady. There seems to be no love lost between them. Another young and handsome man who belongs to an anti-terrorist/ anti-Maoist policing fraternity steps in with his wife. He has just rescued his wife who was kidnapped by Maoists and kept captive for more than a month. The husband refuses to believe that no one has touched her.

Then, a political "arranger and strategist" steps in (Parambrata Chatterjee), eager to help in the case of the little girl's murder but is caught in a communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims who are fighting for compensation for the girl's rape each claiming that the girl belonged to their community. They follow him and barge into the mansion and the strategist gets stabbed.

Somewhere when all this is happening, a baby's cries pull the four youngsters and the landlady to a little female infant thrown outside the door in a dump yard. This baby forms the central focus of attraction, each youngster wanting to keep her with them. She is like an oasis of hope. But is she? Or is she just an example of society's patriarchal leanings?

Before these answers can emerge, the scene suddenly changes to a different ancestral house in the neighbourhood where preparations for Durga Pooja are being done. The aged head of this family suddenly discovers that Durga's hair has fallen off and he knows that the culprit is a little naughty girl, his granddaughter. It takes a bit of time and mental focus to realise that this is the real story while all that happened before was either a play being staged with the curtains falling, or, was a surrealistic world being presented to us to show the position of women in Indian society.

This could be interpreted as Ranjan Ghosh's tribute to theatre where he presents an entire play being performed within the film. The music is out of this world. It is positioned and spaced well and the acting completes the picture. Rituparna appears a bit too self-conscious playing a woman who lives life on her own terms, confident, beautiful, fearless and forthright.

The youngsters are just brilliant in their organic performance. But the incidents are so many that they seem to overlap the previous one before it gets over. The cinematography is outstanding and that is an understatement. The lighting, now dim, now from that single source of the kunda in the center which goes out in the end, now bright and focuses on the different characters, is something to be seen to be believed. The editing is not very demanding as major footage is covered in the ancestral mansion.

The film tends to have overdone the stories drawn from mythology narrated by the sculptor in the beginning but otherwise, rolls smoothly along. But it takes time for the audience to realise the difference between a play being performed within a film on screen.

Cinema is a logical extension of theatre. It is natural therefore, to discover that there are certain commonalities between these two performing art forms. The common factors between the two are: storyline, acting, direction, dialogue, music, space, sound and light. The most important point of unity between the stage and the screen, however, is the audience without which, neither of the two media have any rationale for existence.

Theatre does not need the technicalities of cinema such as editing, sound recording, music recording and so on. It does not need to get into the rigmarole of financiers, distributors, marketing and so on. The dynamics of theatre are different because while theatre has instant and spontaneous audience response, the response to cinema is remote and indirect and can change over a period of time.

Film and theatre owe much to each other. Not only have they developed alongside each other for the last 150 years, but they have borrowed from, exchanged with, and challenged each other along the way. When theatre figured out something that works, film was not far behind and vice versa. As we continue with the digital age, we are finding new and exciting ways to consume film and theatre.

Ranjan Ghose's fourth feature film Mahishasura Marddini has attempted an experiment in creating an innovative form of blending a theatrical performance with a full-length feature film. He has tried to revolutionise how we talk about theatre as not only a medium of words, but that of fully realised productions with visual cues. Mahishasura Marddini offers a classic example of this experiment.