‘The Wager’ Is A Hard Novel

It’s a classical tale of shipwreck, mutiny, death, colonial conquest

Celebrated as a brilliant and deeply disturbing movie at the prestigious 76th Cannes Film Festival held recently, the film has three great actors as its scaffolding: Lily Gladstone, Leonard DiCaprio and Robert De Niro.

DiCaprio has worked with Scorsese in six films now, while De Niro marked his 10th movie with the director. ‘Taxi Driver’, another Scorsese film which went against the dominant current of mainstream American cinema, made in 1976, resurrected the aesthetics of urban angst, alienation and anger, played by a young protagonist, De Niro.

DiCaprio, perhaps one of the finest among contemporary actors in our times, was spotted at the festival with a detached and lost look, as if he has done enough, seen so much, and that there seems no magic anymore in the heady tide of a full moon celluloid night anymore.

Said Scorsese, 80: “I’m old. I read stuff. I see things. I want to tell stories, and there’s no more time. (Filmmaker Akira) Kurosawa, when he got his Oscar, when George (Lucas) and Steven (Spielberg) gave it to him, he said, ‘I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be, and it’s too late.’ He was 83. At the time, I said, ‘What does he mean?’ Now I know what he means.”

The film got a standing ovation, and the audience applauded it with unreserved appreciation. “Mar-tin! Mar-tin! Mar-tin!” -- recited the audience in chorus, while making a French melody of his surname, “Score-sez! Score-sez! Score-sez!”

“What more do you want?! This is the church of cinema, and Martin Scorsese is Jesus! This is a religion, and we have come to pray!” said Mathis Tayssier, 21, a French short film director, quoted in ‘The Washington Post’.

De Niro remembered, according to ‘The Washington Post’, that the seeds for Scorsese to do a movie like ‘Killers’ might go back to the 1970s. The actor remembers when he and Scorsese visited Marlon Brando on his private island in French Polynesia and Brando told them about some film about native Americans he wanted to do.

“Brando had an idea about the thing — I forget what it was at that time — but Marty listened, and the way I remember it is he just felt that was too chaotic and crazy. Never gonna happen,” De Niro said, “So this is something that he finally did in a way that he could do it, the way he would feel was the proper way to do it.”

Few would know that the writer of this incredible film is David Grann, who wrote the book in 2017. The screenplay has been penned by Scorsese along with Eric Roth.

The time and space of the book is not very distant, but it inherits the sinister, diabolical and methodical madness of a society which has been formed on the genocide of tens of thousands of native, indigenous communities, who were methodically and brutally destroyed and displaced from their vast and ancient homeland by nasty, beastly, white settlers.

‘Killers’ is an epic narrative of relentless racism, nasty profit, back-stabbing and greed, and a series of gory murders. The Grann book leaves an acidic, bitter taste about the very identity of White America’s origin. And, yet, it’s a telling tale, a pulsating plot, a deadly drama.

They live in Oklahoma, Mollie and Ernest Burkhart (Lily Gladstone and Leonardo DiCaprio), they are married. This is Osage county. Mollie is an Osage woman, and Ernest, a white man.

They live in oil-rich, black gold territory, a great, native civilisation, skilled and successful. With their inherited native intelligence and wisdom, they knew much before the American oil industry, how to extract the best out of their prosperous underground. That is when the sinister murders move into their lives, like a vicious snake, starting with the murder of Mollie’s sister.

David Grann surely has a knack of weaving epical, original tales from forgotten and buried history, authenticated by meticulous research. He is an American journalist and has worked with ‘The New Yorker’. His first book, ‘The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon’, was published in 2009. It was serialised in ‘The New York Times’, and hit its bestseller list.

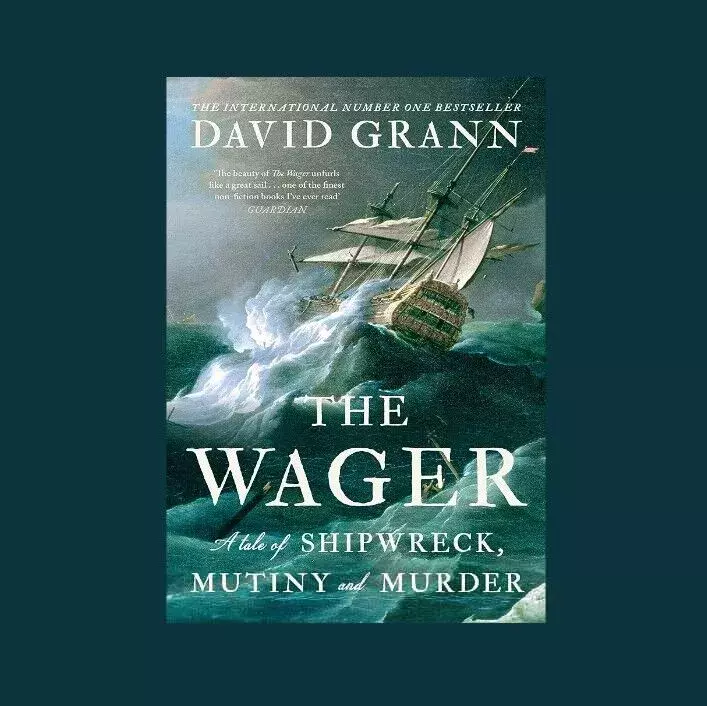

‘The Wager’ is a tiring and hard novel, even for those readers with the insatiable appetite for adventures and long sea journeys with no land in sight for months. It starts with a quote by William Golding: “Maybe there is a beast… maybe it’s only us.”

It’s a classical tale of shipwreck, mutiny, murder, meaningless and death, epidemics and disease, hunger and helplessness, Christianity and faith. It’s also a tale of colonial conquest, humanity and humility, resilience, bravery, leadership and comradeship, love and loss, amidst the turbulence and oceans of eternity in nowhere zones, without maps, outside all geography and history, beyond the reach of the human mind.

And it’s a real story. The book starts with another quote, by Mary McCarthy: “We are the heroes of our own story.”

Remember Robinson Crusoe? Alexander Selkirk, a British officer, was marooned off Patagonia in the 18th Century, a lost and solitary island without any civilization, food or shelter, somewhere in Latin America. It was a brave, extremely difficult and inspiring story. His life and times was the inspiration behind Daniel Defoe when he wrote another classic: ‘Robinson Crusoe’.

Coincidentally, the British convoy of armoured ships, with the sole purpose of defeating the Spanish on sea and looting their treasures, was also chasing the dream island of Robinson Crusoe. Even American author, Herman Melville, was inspired by this incredible story of castaways in a no-man’s land surrounded by nothing but infinite saline waters, which they named after their unfortunate ship: The Wager.

Apparently, during his long travels and meticulous research, Grann travelled in a small boat to this island, while listening to Melville’s ‘Moby-Dick’.

Ferocious storms, blizzards, ceaseless snow stalked The Wager. Plus, endless epidemics. Slow, tortuous deaths. But they refused to turn back, led by their commander: Captain Cheap.

Writes Grann: “As the scourge invaded the sailor’s faces, some of them began to resemble the monsters of their imaginations. Their bloodshot eyes bulged. Their teeth fell out, as did their hair.

“Their breath reeked of what one of Byron’s companions called an unwholesome stench, as if death had already come upon them, The cartilage that glued together their bodies seemed to be loosening. In certain cases, even old injuries reemerged. A man who had been injured at the Battle of the Boyne, which took place in Ireland more than 50 years earlier, had his ancient wounds suddenly break out anew…”

In the Wager Island, as castaways, after their ship was ravaged by nature’s apocalyptic fury, they would go without food and water for days, turning into emaciated reeds. The marooned were still under the command of an injured Captain Cheap, courageous leader of the defeated mission. They were still subjects of the British empire, and operated under their law.

This is when rebellions started breaking out. Some made their own camps with their own captains. Others stole food from the collective tent. While others prepared to escape this destiny by making their own boat.

A soldier had a dog which he loved. He spoke to him and slept with him. One day, his comrades came and asked for the dog. He knew why. They killed the dog and ate him up. Finally, mad with hunger, he, too, was forced to eat the same flesh. Some took to cannibalism.

There was no hope. They were all destined to die on Wager Island. They might all end up killing each other. Nothing came from the vast ocean. Except storms, freezing cold, hunger, hopelessness.

Then arrived a miracle. Human beings appeared on the shore. Native, beautiful, generous, indigenous communities, who knew the oceans and the islands like the back of their hands.

Writes Grann: “European explorers, baffled by how anyone could survive in the region – and seeking to justify their brutal assaults on indigenous groups – often labelled the ‘Kawesqar’ and other canoe people as ‘cannibals’, but there is no credible evidence of this.

“The inhabitants had devised plenty of ways to find sustenance from the sea. The women, who did most of the fishing, tied limpets to ropy sinews and dropped them in the water, waiting to jerk a prize upward and grab it with one hand.

“The men, responsible for hunting, lured sea lions by singing softly or slapping the water, then harpooned them when they rose to investigate. Hunters set snares for geese that wandered on the grasslands at dusk, and they used slingshots to pick off cormorants. At night, the Kawesqar wave torches at nesting birds to blind them before clubbing them.”

Magnanimous and wise as they were, they arrived one day with their families, made homes with tree branches and leaves, and settled down in a clean, organised colony in the neighbourhood with the sailors.

They gave them food, sustenance, shelter, even a sheep. And what did they get in return from some of the unethical white settlers? Cheating. Bad faith. Betrayal. Even their women were not spared.

So, one day, the sailors got up in the morning to find that the Kawesqars had disappeared. Vanished into the blue. They were, thus, left to their condemned and exiled destiny yet again, even as a full-fledged mutiny blew up against a rigid Captain Cheap, with him becoming more and more isolated.

The fabulous dimension of this hard and incredible journey, which explores the innermost nuances of the human mind and body, is the meticulous documentation done by some of the sailors, including the lowest in the lower decks.

They would compile daily notes, and some of them published these bulky volumes, with them becoming bestsellers in Britain, subject of much gossip, romance and speculation, and, also, as evidence of the reality of the journey.

Most of them were finally dead in unknown islands, marooned. A handful were able to escape the hand of fate, and, with the help of local tribes, some of them reached Spain, their enemy country. Imprisoned, they were treated with dignity, and, thereby, allowed to sail to England.

Almost all of them got acquitted by the British courts of the time. Captain Cheap survived and returned to much glory, wealth and fame. Others disappeared in the receding waters of history.

The ‘London Guardian’ wrote, in its review: “We make our stories, until they make us. So many of Grann’s predecessors wrote of colonial adventures in a way that glorified violence, exploitation and enslavement.

“But, recognising the power of story, Grann seeks to burnish nothing, instead, presenting the truth. He fixes his spyglass on the ravages of empire, of racism, of bureaucratic indifference and raw greed. In doing so, he frees himself to acknowledge the valour, the curiosity, and the sheer adventure of the age.”

Title: The Wager

Author: David Grann

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Price: Rs 799