‘India That Is Bharat’ -The Indian Constitution Has Stood The Test Of Time

Name change represents fundamental shift in policy

As both Republic Day on January 26, 2024 and the next general elections in 2024 beckon, it is worth our while to look at the Narendra Modi phenomenon through the lens of the debate over India Vs. ‘Bharat’ and the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) possible move to expunge the word India from Article 1 of our Constitution which says “India that is Bharat….”.

It is useful upfront to define what the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Hindutva propelled “idea of Bharat” signals from the Modi government’s point of view: an indigenous, homogenous entity, economic and geopolitical strength, and an unwillingness to accept internal or external critique. This can be contrasted with the “idea of India” which was a Nehruvian construct of tolerance and pluralism at home and internationalism overseas.

At the outset, let me acknowledge some of the Modi government’s achievements (eg. digitisation despite the BJPs stiff and vocal opposition to Aadhar when it sat in the opposition benches since digitization would not have been possible without it); a broadly stable macro environment; high economic growth rates recently; better ground level implementation of certain programs, proactive leadership in some areas).

Let me also clarify that this is an opinion piece more on the desire of the Modi government to change India’s name to ‘Bharat’ (the Hindi version of the name), and possibly expunge the mention of India from Article 1 of the Constitution. I argue below that this will be much more than a name change which we must comprehensively debate by taking stock of the many changes in policy under the current government.

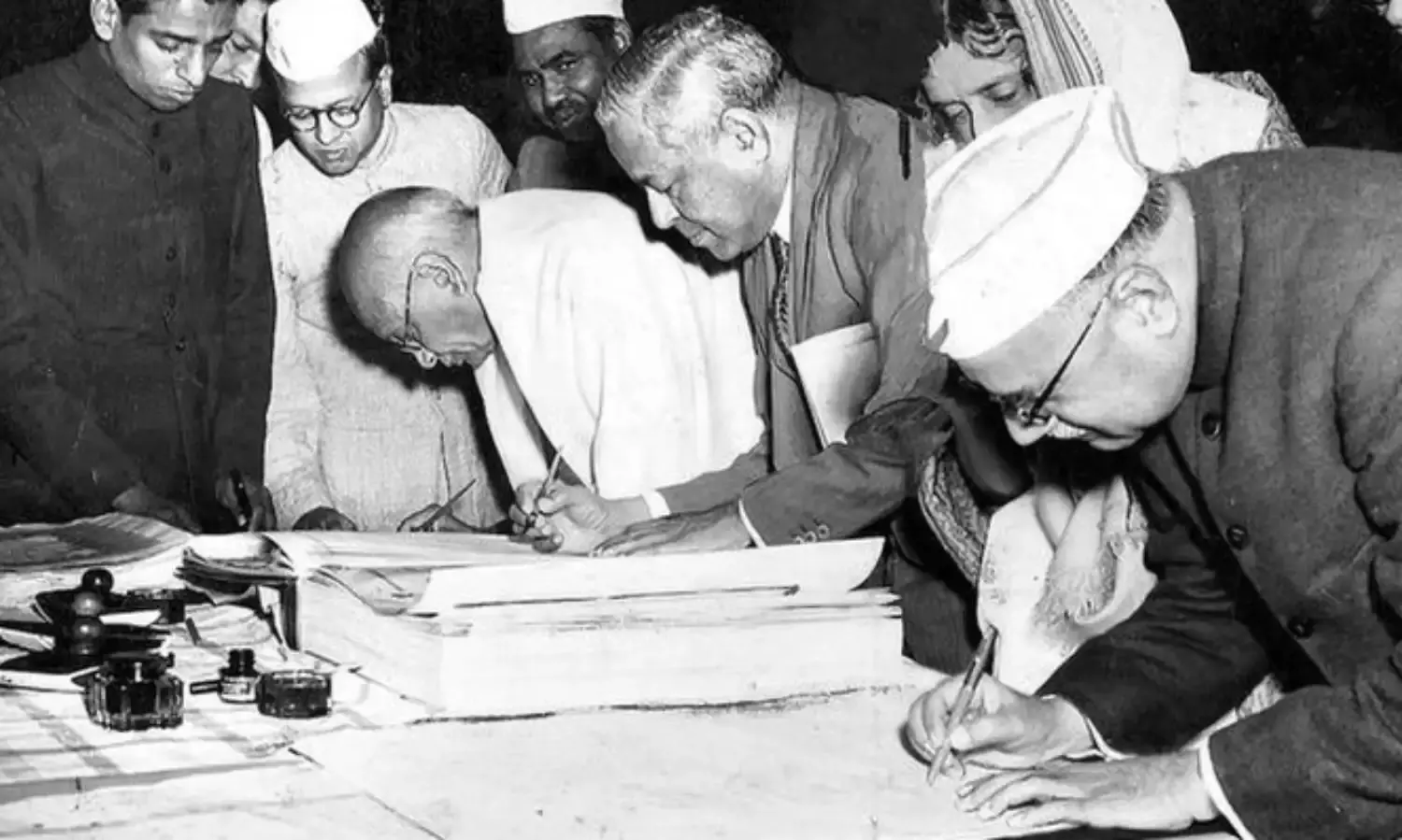

India, through and as a result of its freedom struggle from British rule in August 1947 was formed as a genuinely democratic and secular state, its two most defining characteristics. There was broad consensus on this and its1950 Constitution is widely regarded as one of the world’s best and forward looking.

Even though the word ‘secular’ was only added in 1976 and not included initially after much deliberations by the Constituent Assembly, it is broadly agreed that in practice India has been relatively and largely secular from its Independence till recently under the current government.

The Constitution gave rise to independent political and development institutions like the Election Commission, Planning Commission, Supreme Court and broader judicial system, the Lok and Rajya Sabha and the Government of the day, together with scope for a real democratic opposition and free civil society.

This “idea of India” was not just an aspiration but a reality for much of our journey since Independence. A contemporary, topical example which is a product of this India is our cricket ‘Team India’ which played in the recent World Cup final on November 19 and clearly represents that India.

For example, Rohit Sharma, the captain, sounds like a North Indian name but he comes from Mumbai, Shreyas Iyer’s ancestors are from Kerala but he is from Maharashtra, K.L. Rahul is Mangalorean, R. Ashwin is a Tamil Brahmin while Shubman Gill and Virat Kohli are from the Punjab (ref. ‘The Republic of Team India’ by Mudar Patherya).

A significant part of the graceless and raucous crowd in the Narendra Modi stadium in Ahmedabad, Gujarat where the cricket finals were played, some of whom even indulged in uncalled for religious sloganeering,’ stand for ‘Bharat’.

‘Bharat’ has undermined or compromised most if not all the Independent institutions established when India came into existence. These include but are not limited to the Election Commission and the Supreme Court.

The Planning commission which was a worthwhile institution despite some failings has, on the other hand, been abolished. ‘Bharat’, at one level, represents the interests of the Hindi speaking belt, making it the predominant one, especially dominating over the South of the country, reducing unity at this fundamental level.

It serves to make the country both vulnerable and divided as never before in this still relatively new millennium when such divisions in India should have been minimised or left behind forever.

This trend could get worse with the redrawing of electoral boundaries due in 2026. For example, while in 2019, the BJP won 303 of the 542 seats in the Lok Sabha with 37 percent of the vote, a political pitch during the redrawing of the electoral map in 2026 could lead to 753 seats in the Lok Sabha with most new ones going to populous Northern constituencies where the BJP dominates.

On the domestic front, religion has been politicised as never before. Building on what began in Ayodhya in the early 1990’s, the dominant religion, Hinduism, has been promoted to the exclusion of all other faiths in what was an erstwhile secular India.

What used to be seen as a personal faith to be freely practiced in the sanctity of your house, temple, church, mosque or gurudwara has become a public display, but only for Hinduism. Islam in particular, but also Christianity, have borne the major brunt of the venom of the Indian state.

A certain vocal and strident section of the masses have become more brazen in both their display of Hindutva (an ultra-nationalist and conservative non-pluralistic version of Hinduism which as a religion or philosophy is, in its essence, pluralistic, representing a great forgone civilisation) and opposition to Islam particularly through mob lynching’s and other ugly public displays.

Also on the domestic front, development as a concept has for the last five years been reduced largely to physical infrastructure development, as in Gujarat where Prime Minister Modi developed this approach whilst Chief Minister (eg.the Narendra Modi Stadium where the World Cup cricket finals were played this month).

Notwithstanding the importance of quality physical infrastructure like roads, schools and hospitals on which India has, no doubt, been a laggard and needs more high quality ones, the essential and arguably more important soft and intangible aspects of development such as social and employment guarantee programs pioneered well before the Modi government have been neglected.

While certain programs like the Prime Minister’s Garib Kalyan Aan Yojana (PMGAY) have been extended for five years, Cabinet approval was provided only in the last week of November 2023. This program indicates more of the micro economy’s weakness than the government’s commitment and it seems to be timed to win the 2024 election.

The ‘K’ shaped consumption and recovery curve which applies to India’s economy clearly favors the 1 percent in the economy (buyers of Tesla, Lotus for cars and Apple, all of whom the government is wooing) and not the ordinary man or woman.

Nervousness about the 2024 elections abounds. In particular, the government’s roll out of the Bharat Dal and Bharat Atta programs, selling subsidised pulses and flour to the public before the elections is a clear indication of its nervousness before the elections.

The LPG subsidy has also been hiked twice in just over a month, the first hike of Rs 200 per cylinder was income blind while the second hike of Rs 100 was more targeted at beneficiaries of the Prime Minister’s Ujjwala Yojana (households without LPG but eligible for electricity connections).

At a macro level, the economy has been relatively stable with an economic growth rate of 4.5 percent in the fiscal year’s Q4 2022-23, 6.1 percent in Q1 2023-24 and an impressive 7.6 percent in Q2 2023-24, the highest growth rate among G-20 economies, despite the skewed ‘K’ shaped consumption and recovery curve in favour of the rich 1 percent. The main driver of this economic growth has so far been public investment.

If that slows as it probably will because of India’s worrying fiscal scenario, it will need to be replaced by other drivers of growth which are quite weak at present. India, however, will need both to sustain this recent growth rate of between 7-8 percent per annum and, even more importantly, make it much more broad based and focused on the poor than it currently is.

Moreover, India’s estimated per capita income at its record high of USD 2085 (World Bank, PPP, 2022) is still only 17 percent of the world’s average with an inflation rate which continues to be higher than most countries. India is ranked 133 out of 194 in per capita GDP. its per-capita GDP is less than one-fifth that of China and less than 1/32 that of the USA, even though it is the fifth largest economy in the world, and is projected to be the third largest economy by 2030 with an aspiration to attain a per capita income of USD 21000 by 2050, according to a recent article ‘Mint’ that quoted Aranu Chakraborty, Chairman of HDFC Bank.

Furthermore, on UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) which is a globally accepted much more comprehensive measure, India’s ranking and value was 132 and 0.633 in 2021, declining from 0.645 and 131 in 2020. It is rare for a country to drop in its ranking. Its ranking on the Global Hunger Index is also very low at 111 out of 125, placing it in the last 15.

Former Finance Minister P. Chidambaran in early December presented Periodic Labour Force Participation data in Parliament, which indicated that the worker participation rate was only 46 percent with only 22 percent for females. Effectively, this overall participation rate means that only 23 percent of Indian people work and the declining female labor force participation rate is a real concern.

Also worrying is the unemployment rate for the 15-24 year age-group which is 23.22 percent while for graduates under 25 it is a significant 42 percent (Indian Express, December 2, 2023).

The ill-advised demonetisation and its aftermath have had serious consequences for cash as a currency of exchange doing little to curb the black money market which it was touted as aimed at. Increased bank accounts and money in the formal banking system which has led to a degree of financial inclusion especially for women, (the Jan Dhan Bank accounts had a balance of Rs 1.99 lakh crores as at March 31, 2023) and digitisation (dependent on Congress’ Aadhar scheme), and its mainstreaming which has led to direct transfers of some government benefits to the poor have been its main benefits.

Anecdotal evidence also suggests that this had led to a decrease in petty corruption. This has led to the Modi government taking credit for all of this and more while genuine credit should at least be shared with the previous Congress government under whose tenure Aadhar was devised and rolled out without which these initiatives would not have been possible.

On the social infrastructure front, the recently approved emergency allocation of Rs. 10,000 crores for a previous Congress government's Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) due to the enormous demand for work by rural youth and others is welcome but it indicates a direct weakness in the rural economy and, in any case, builds on and thereby acknowledges the importance of previous Congress government initiatives in this area.

While all these recent programs in the social area are welcome, many of them build on previously existing initiatives of Congress governments and in any case do not represent new imagination (I am including the BJPs support for MGNREGS as an indication that they cannot do better than what the Congress government already did in this critical area). More importantly, coming so late in the Modi government’s tenure in office, they must be viewed as 2024 election related freebies and equally importantly.

While gender discrimination has reduced in an already polarized discriminatory environment on gender issues against women, bisexuals and other sexual minorities in particular (the 2023 Global Gender Gap Report of the World Economic Forum ranks India 127 out of 146 countries in terms of gender parity as compared to 135 out of 146 in 2022), there is still a long way to go.

More broadly, the Modi government and its 'Bharat's' narrow definition of development compared to "Development as Freedom" (as noted by Dr. Amartya Sen, Nobel Laureate and internationally acclaimed Indian origin academic and philosopher) has placed India on a dangerous path.

The situation is even more precarious because of increasing human rights abuses and violations of both a religious and other kind. These now span the entire spectrum and are difficult to cover in a short opinion piece.

Needless to state, they are wide-ranging and deep, and therefore undermine our defining democracy and secularism as well as our 1950 Constitution. They are frightening in any real democracy, especially measures that are specifically aimed at the political opposition and credible journalists in our country.

India ranked 111 out of 165 in 2020 in the Cato and Fraser Institute Human Freedom Index, down from its 94 ranking in 2019. On the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index, its ranking deteriorated to 161 out of 180 countries in 2023, down from 150 in 2022 and 142 in 2021. Its 2023 score was 36.62 out of 100, down from 41 in 2022 and 53.44 in 2021.

There are also international and foreign policy ramifications which are potentially serious. A key question which needs to be asked is whether Prime Minister Modi or others in his cohort are serious about the “idea of Akhand Bharat” and if so, what this entails and covers?

How will this be viewed by our immediate neighbors in South Asia in what India has regarded as its backyard? “Akhand Bharat” seeks to encompass modern-day Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Tibet as one nation what does it mean for them who may justifiably wonder if ‘Bharat’ has expansionist ambitions to extend its Hindi speaking belt to encompass them.

More broadly, foreign policy has, at one level, been redefined to support other narrowly religious and nationalistic states such as Israel, undermining India’s long-standing non-aligned and nationalistic (i.e. anti-colonial) credentials which India had sustained since its independence in 1947 till the Modi government came to power.

Support for Putin’s Russia by continuing and even increasing the purchase of discounted Russian oil and other commodities (with Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar even recently presenting the oil purchases proudly as stabilising global oil prices) and through the nature of its vote or abstention on many UN Resolutions condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine only shows that India is not a responsible global player and therefore, not ready to assume the global responsibilities of being a permanent member of the UN Security Council, its top foreign policy priority.

The obvious fact that all current Security Council permanent members (eg. Russia, US, China, France and the UK) also do not often enough show global responsibility does not excuse aspiring members like India from showing such responsibility since the entrance bar for them must, of necessity, be higher in this new millennium.

It must be said, however, that India has a more legitimate claim to permanent membership than at least France and the UK and perhaps Russia who should not even be permanent members of the UN Security Council in this new millennium since the world has changed so much since the Second World War ended and the UN rose from its ashes with the current permanent membership.

What has kept Modi and Shah going is a sizeable, silent and increasingly confident and therefore often not so silent Hindu majority.

Credible poll results have shown only a 30 percent+ hard core Hindutva voting base for the Modi government. Nevertheless, substantial portions of this cohort are increasingly confident and often quite outspoken. Together with the silent component they are complicit in the government’s policies and endeavors.

A resulting tragedy for India is not just that its communal harmony (which was never as good as desirable even under Congress rule) has significantly deteriorated but that a significant number of bright youngsters and other mid-level and even senior professionals with the opportunities or means are fleeing ‘Bharat’ for greener pastures, particularly in the West.

This is brain drain on a significant scale whose consequences have yet to be fully felt or understood but it is clear that they will not be positive for the country in the mid to long-term. This brain drain is also very different from the substantial “brain circulation” of the past when such youth or middle-aged Indian professionals often maintained a base in India but went overseas for years to gain new skills and earn money, both of which they brought back and put to good use in India to its overall benefit.

The India Vs. ‘Bharat’ debate must inevitably take account of the issues briefly discussed in this opinion piece if there is to be a serious debate on the desirability and wisdom of such a fundamental name change for the country through a Constitutional amendment which results in the deletion of India from Article 1 of the Constitution.

It is, indeed, not just a name change for the country but represents a fundamental change in the way India has been operating for at least five years before the name change to ‘Bharat’ was suggested. As such, it is likely to be viewed with consternation and even alarm by both many citizens of India as well as its neighbors and more widely, internationally in at least some important and influential circles. This should be of great concern to India’s current 1.4 billion citizens and will also negatively impact future generations.

As we approach Republic Day on January 26, 2024 we must also consider whether it is wise to reconsider fundamental aspects of our Constitution. The Indian Constitution has stood the test of time and is widely acknowledged by the UN and others as among the world's best.

The debate on changing India's name to 'Bharat' only without any mention of India in Article 1 of the Constitution should also not become a diversion from the very real and hard policy and practical issues confronting us as we proceed in this millennium and more specifically to the forthcoming 2024 elections.

Kamal Malhotra is an international development consultant, and a Senior International Research Fellow at Boston University's, Global Development Policy Centre. Views expressed are the writer’s own.