The Reluctant BRICS Traveller

India trims its sails to suit the Global South winds

India became a beacon of hope for the Western media for a short while in the run-up to the BRICS Summit in Johannesburg — a potential dissenter who might derail the grouping’s acceleration toward a “de-dollarisation” process.

Reuters floated a rumour that Prime Minister Narendra Modi might not attend the summit in person, which of course was an excessive case of wishful thinking but called attention to what a high stakes geopolitical game BRICS has become.

Such paranoia was unprecedented. If up until last year, the Western game was to mock at BRICS as an inconsequential club, the pendulum has swung to the other extreme. The reasons are not far to seek.

At the most obvious level, there is great sensitivity in the Western world that the massive effort through the past 18 months to weaponise sanctions against Russia not only flopped but boomeranged. And this is at a time when the United States’ morbid fear of being overtaken by China peaked — burying the global hegemony of the West since the “geographical discoveries” of the 15th century.

The recent years witnessed a steady strengthening of the Russia-China partnership, which has reached a “no limits” character, contrary to the Western calculus that the historical contradictions between the two neighbouring giants virtually ruled out such a possibility. In reality, Russia-China partnership is shaping up as something bigger than a formal alliance in its seamless tolerance of the optimal pursuit of each protagonists’s national interests while concurrently supporting the core interests of both sides.

Thus, any format in which Russia and China play a lead role, such as BRICS, is bound to be in the US’ crosshairs. It is as simple as that. The New York Times called the BRICS expansion “a significant victory for the two leading members of the group, increasing China’s political influence and helping to reduce Russia’s isolation.”

It drew comfort that the group is heterogeneous and does not have a clear political course, “except for the desire to change the current global financial and management system, making it more open, more diverse and less restrictive.”

This is the whole point. The Indian analysts are missing the wood for the trees. The Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov disclosed to the media that behind closed doors, the Johannesburg summit had “quite a lively discussion” [read divergent opinions] but reached a consensus on the “criteria and procedures” of BRICS expansion, which he outlined as follows:

“The weight, prominence and importance of the candidates and their international standing were the primary factors for us [BRICS members]. It is our shared view that we must recruit like-minded countries into our ranks that believe in a multipolar world order and the need for more democracy and justice in international relations. We need those who champion a bigger role for the Global South in global governance. The six countries whose accession was announced today fully meet these criteria.”

Later, after returning to Moscow from Johannesburg, Lavrov told the Russian state television two important things:

“We [BRICS] don’t want to encroach on anyone’s interests. We simply don’t want anyone to hamper the development of our mutually beneficial projects that are not aimed against anyone.” Western politicians and reporters “tend to wag their tongues, while we use our heads and [engage in] concrete issues.”

There is no need for BRICS to become an alternative to the G20 now. That said, “the formal division of the G20 Group into G7+ and BRICS+ is taking a practical shape.”

Unless one is myopic, BRICS’ sense of direction is there for all to see. The grumbling and hand-wringing about the logic of BRICS expansion is complete nonsense. For, the unspoken secret lies here, as a leading Russian strategic thinker Fyodor Lukyanov wrote in the government daily Rossiyskaya Gazeta:

“We can hardly talk about an anti-Western orientation — with the exception of Russia and now, perhaps, Iran, none of the current and likely future [BRICS] participants openly wants to oppose themselves to the West. However, this reflects the coming era, when the policy of most states is a constant choice of partners to solve their problems, and there may be different counterparts for different problems.”

This is the reason why India, which carefully protects its line of “multi-alignment” — that is, cooperation with everyone — is also satisfied with a large and heterogeneous BRICS. Delhi is least interested in strengthening antagonistic sentiments within the BRICS community. The Indian commentators cannot grasp this paradox.

Indeed, the pragmatism in admitting three major oil producing countries from the Gulf region (Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE) only signals what Lavrov meant by the “projects” and “concrete issues” that BRICS is grappling with — principally, creating a new international trading system to replace the 5-centuries old system that the West created, which was geared to transfer wealth to the metropolis and enabled the latter to get fatter and richer.

Basically, this is today about tackling the phenomenon of the petrodollar, which is the pillar of the western banking system and at the very core of the “de-dollarisation” process that the BRICS is aiming at. Suffice to say, the curtain is coming down on the Faustian deal of the early 1970s that replaced gold with American dollar and ensured that oil would be traded in dollars, which in turn required all countries to keep their reserves in dollars, and eventually turned into the principal mechanism for the US’ global hegemony.

Put differently, how is it possible to roll back the petrodollar without Saudi Arabia being at the barricades? That said, it is also well understood by all member states, including Russia and Saudi Arabia, that while BRICS is “non-western,” a transformation of the BRICS into an anti-Western alliance is impossible. Quintessentially, what we are seeing in the BRICS’ expansion, therefore, is its transformation into the most representative community in the world, whose members interact with each other bypassing Western pressure.

This is enough for a start, as the reaction in the Western countries to the outcome of the Johannesburg summit testifies. The leading German daily Suddeutsche Zeitung noted that with this limited expansion itself, BRICS has gained “significant geopolitical and economic weight. The question now is how the West will react to this.”

A top official at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Caroline Kanter told the daily, “It is is obvious that we [Western countries] are no longer able to set our own conditions and standards. Proposals will be expected from us so that in the future we will be perceived as an attractive partner.”

France’s Le Figaro wrote that the “enthusiasm” of some 40 countries for BRICS membership “testifies to the growing influence of developing countries on the world stage.” The Guardian highlighted expert opinion that BRICS expansion is rather “a symbol of broad support from the global South for the recalibration of the world order.”

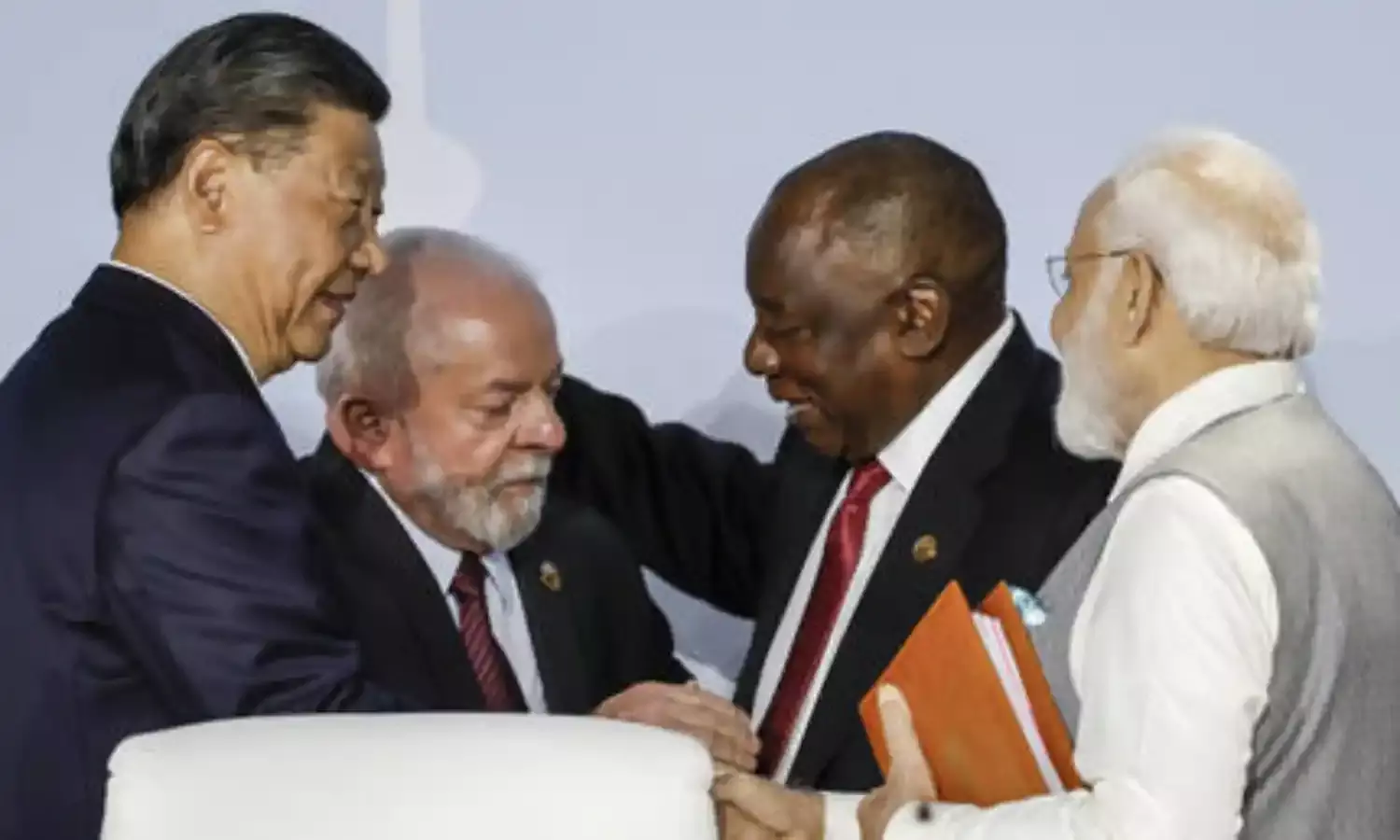

At the same time, the bottom line is that BRICS expansion is perceived in the West as a political victory for Russia and China. Nonetheless, despite its tensions with China, India did the right thing by trimming its sails accordingly while sensing the winds of change and anticipating a new dawn for BRICS cooperation that could inject new vitality into the grouping’s functioning and further strengthen the power of world peace and development.

It is about time the government rethinks the viability of its strategy to hold the relationship with China hostage to the border issue. The BRICS Summit highlighted that China enjoys big support from the Global South. It is quixotic, to say the least, to act as a proxy of the US to contain China.

India will find itself in a cul-de-sac by dissociating itself from the issue of local currencies, payment instruments and platforms simply because China could be a beneficiary of a new trading system that is part of a more just, equitable and participative global order. India risks alienating the Global South who are China’s natural allies, by turning its back on the BRICS’ core agenda of a multipolar world order.