Indian Media Harassed, Social media Weaponised: IFJ

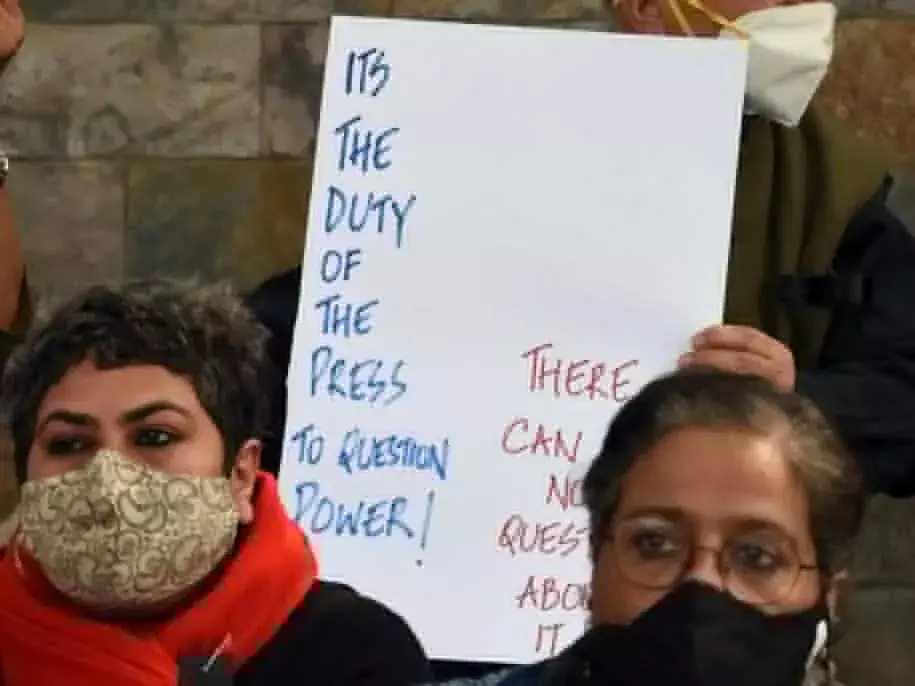

International Federation of Journalists slams India’s use of law enforcement agencies to muzzle media

The South Asia Press Freedom Report of 2023 of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) has slammed the Indian government’s use of the law enforcement agencies to muzzle the media and decried the weaponisation of the social media.

The report, which covered press freedom in South Asian countries in 2022, said about India that the “concentration of legacy media houses in the hands of a few corporate houses saw the simultaneous boom in social media propagation of ‘news’. This unregulated and free-for-all space was systematically planted with propaganda. The weaponisation of social media, particularly WhatsApp, by political parties was rife.”

“A section of the media was identified as being pro-government while others were labelled hostile or “anti-national” and subjected to harassment in various forms, including being foisted with criminal cases.”

“The overreach of law by enforcement agencies in India deployed by the government to conduct raids, searches and “surveys” on intransigent media houses marked the period under review. On October 31, 2022, the police conducted searches at the homes and offices of the editors and a reporter of independent news website The Wire following a complaint by the national spokesperson and head of the party IT cell of the ruling party. The Editors’ Guild of India termed the “surveys” as “excessive and disproportionate”.

“In February 2023, Income Tax authorities raided the offices of the BBC in Delhi and Mumbai citing income tax violations. However, the provocation for the raids appeared to be the release of a two-part documentary series titled “India: The Modi Question” critical of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The government blocked the documentary and anyone found screening it was penalised.”

“Another routinely used method of harassment was to file multiple First Information Reports (FIRs or police complaints) against journalists for the same offence across states. Many journalists were arrested under the draconian National Security Act, or Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) which saw them incarcerated without trial or bail for long periods.”

However, the report noted the upholding of press freedom by the judiciary in some cases was welcome. The Supreme Court on April 5, 2023, quashed the Centre’s telecast ban on news and current affairs channel, MediaOne, declaring that an independent press is necessary for robust democracy.

Another ray of hope in India was the order passed by the Supreme Court in May 2022, putting the contentious sedition law on hold and asking the Union and state governments not to register any fresh case invoking the offence.

The report said that 2022 also saw media ownership in India get concentrated in the hands of corporate houses that acquired the few independent voices that remained in the electronic media.

“The takeover of NDTV, a popular independent television news group, by a corporate house perceived to be close to the government, was one such instance and led to a number of staffers and founder directors quitting the organisation. Media houses already owned by other corporations are restricted in their reporting due to their dependence on government largesse.”

During the pandemic many journalists lost their jobs, which many could not get back after the pandemic, the report said.

“The magnitude of the layoffs was revealed only when journalists began to share termination letters on social media. Most of those who lost their jobs were not reinstated even after advertisement revenues stabilised in the post-pandemic period. Court battles too seemed hopeless, given the dilution of the Working Journalists Act, which offered a modicum of legal protection against such arbitrary dismissals.”

In South Asia, as a whole in 2022, there were 257 incidents of harassment of journalists, 76 arrests or detentions, and 13 killings, according to the report.